Two months have passed since writing my last chapter. In that time, my hope has been tested, a sail beating against a gale, a fissure forming at the seams—no one conceiving if the threads will rupture and give in to the sea.

Two weeks after completing the sixth and final treatment of BCG immunotherapy, my local urologist, Dr. Julio Slongo, put me under to scrutinize the results of the therapy. What he found was hope’s nemesis: a three-centimeter tumor had returned. The immunotherapy had failed; I still had bladder cancer.

That news engorged my throat. But that was not the end of bad news.

Shortly after my last treatment of immunotherapy, my anus seemed to constrict. I could still defecate, but the results were tiny fragments like miniature sand crabs, each evacuation accompanied by a sharp stab. With time, the pain was not limited to my anus. The ache expanded and deepened. It felt like my pelvis was on fire. I made an appointment to see a colorectal surgeon. Unfortunately, the first available time slot was six weeks out. During the interim, the unrelenting pain ranged between six to eight on a ten-point scale. Every tick of the clock was another prick, reminding me I was still alive but reluctantly.

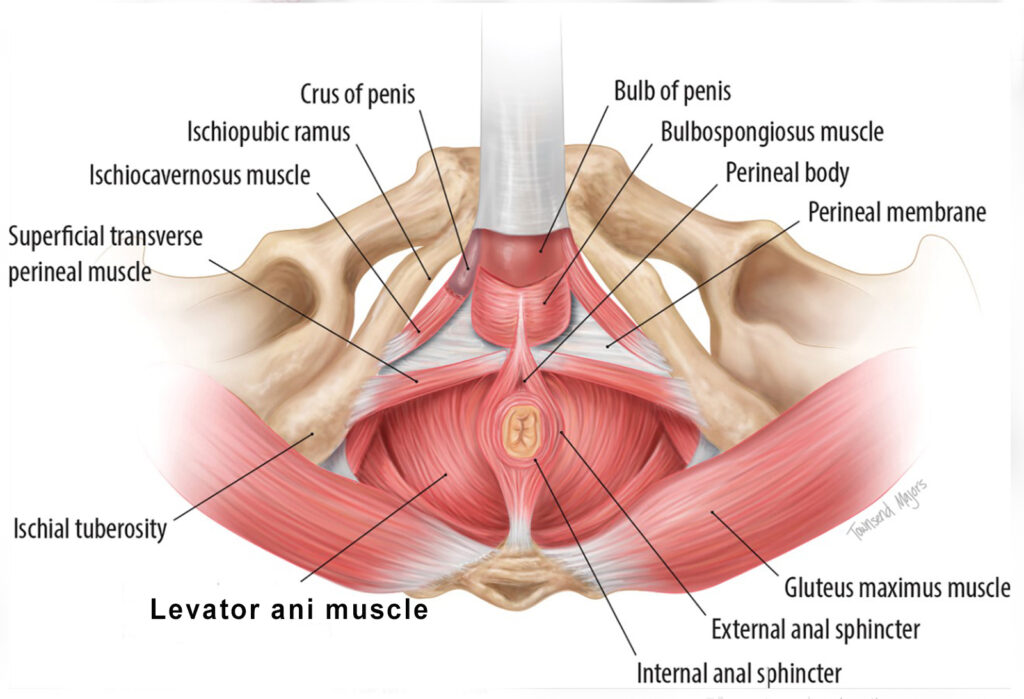

I was finally able to see the colorectal surgeon on January 5, 2023. After a short examination, the surgeon said the left side of my levator muscle had seized. I soon learned the levator ani muscle is a broad, funnel-shaped sheet that surrounds the rectum, tapers down to the anal canal, and merges with the voluntary anal sphincter. The problem was systemic: when the levator clutched, it restricted the anus, which reduced the numerous trips to the toilet to a pathetic series of high-achiever rabbit pellets.

“What causes the spasm?” I asked.

“No one really knows,” the surgeon said. “Some think it’s a reaction to stress.”

“But why me?” I quipped. “My life is stress free.”

The doctor locked on my gaze, but only for a second. “Is that sarcasm?”

“The technical term is irony,” I said under my breath.

I don’t think the surgeon registered the nuance. In any case, there was no humor in his tone. “I recommend injecting the levator muscle with Botox.”

“What does that do?” I asked.

“It paralyzes the muscle.”

“Is that a good thing?” I asked. “It really don’t care if my sinews are wrinkled.”

Not even a whisp of a smile from the surgeon. “If it can’t function, it can’t spasm. And if it can’t spasm, it can’t cause pain.”

With that the surgeon left—not one for idle chitchat.

Later, I was told the procedure was scheduled for January 16. Great. Only eleven more days of constant pain. In case you’re wondering. That was sarcasm.

***

After the procedure, the pain never let up. I was living on Tylenol during the day and oxycodone at night. I began to think there must be another way. I scoured the internet and came across a term called pelvic floor physical therapy, reputed for relieving pain.

The words “reliving pain” departed from my computer screen, swirled around my head, and drilled into my heart. I immediately called the colorectal surgeon and asked if they could refer me to a pelvic floor therapist.

“Oh, of course,” an assistant said. “We do that all the time.”

And it didn’t occur to you to mention it to me. It was only a thought. I didn’t want to squander my chances of getting relief.

“Please refer me,” I said.

A week later, I sat in the examination room of a pelvic floor rehabilitation therapist. I never knew there was such a specialty. But I’m glad I know now.

Her name was Cassie McCook. I liked her immediately. Even though her nose and mouth were covered by a post pandemic mask, I could tell by the flash in her eyes she was present, engaged, and seemingly happy to be at work.

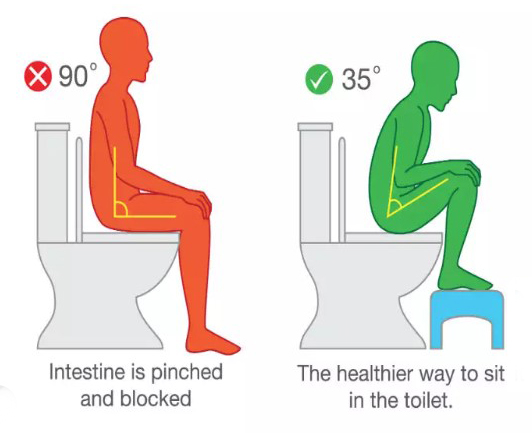

In the first session, Cassie taught me how to poop. You might think I would have figured that out by now. If so, you’d be wrong. There is a way of transferring wastes down the chute without pain. In brief, you set your feet on a five-to-seven-inch-high platform in front of the toilet and spread your knees, which conjures up the physical geometry of taking a dump in the woods.

The second step is the breathing. You fill your lungs to push the diaphragm down, which compresses the bowels through the anal duct. (I’m trying to be polite here.) You do not hold your breath. When you breathe in, you keep your abdomen expanded, restricting the waste from slipping back up the chute.

Though it may sound complicated, I assure you it works.

On the second session, Cassie said, “I want to try to relieve your pain.”

In brief, I said, “Yes.”

“I’m fully qualified to do rectal exams and therapy.”

“Uh huh. What did you have in mind?”

“I think I may be able to relieve the pain by massaging the tightest section of the levator muscle. You can think of me as a spa masseuse.”

“Can you do a pedicure at the same time?”

“I can even wax your swimsuit line if you like.”

Although I liked her humor, I said, “I think I’ll pass.” I stood to relieve the pain from sitting too long on my tailbone. “Let me get this straight. You’re going to put your finger up my rectum, search the perimeter for the hot spot, and press into it.”

“Understand the pressing won’t be all that forceful,” she said. “We are talking about my forefinger. Not my elbow.”

“Got it.” I swept my hand over my tingling scalp. “Is your fingernail clipped?”

She presented her forefinger, which had a splash of black polish, chipped around the edges. “Down to the quick,” she said.

She asked me if I wanted a witness in the room; I said, no. She left the room; I undressed from the waist down and flipped a sheet over my bare tush.

A moment later, she returned, slid her finger into my bum, and, drawing from first-date yammering, asked about my vocation and avocations. Knowing her intent, the diversion was not particularly helpful. The muscle manipulation was disturbing at best, agonizing at worst.

When it was done, her tone was timid. “Are you all right?”

“I’m okay,” I said. “But, with malice toward none, I’m glad I’m nobody’s girlfriend doing hard time at the big house.”

On a chuckle, Cassie said, “I’m happy for you too.”