On February 6, 2023, I received a video call from my University of Washington Medical Center oncologist, Dr. Grivas. Also in attendance were three of my support-team neighbors—Bob, Alan, and Elaine—and my cousin, Basil, from Denver.

A word about Dr. Grivas. There are doctors who speak two hundred words per minute, which is speedier than normal. When in their offices, you hear the clock ticking, despite the urgency and solemnity of your own illness. Dr. Grivas was not like that. On average, Americans speak 125 to 150 words per minute. Dr. Grivas was on the low end of that scale—and for that, I was always grateful. His pace was slow enough for me to absorb the nuances of his words. More importantly, his style was the perfect balance between compassion and medical competence, both of which were formidable.

He dropped his mask so I could more easily register the impact of his recommendations. He repeated what Dr. Seymour had already told me: that four or five tumors had encased my rectal canal. I had stage-four cancer. The only treatment was chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and possibly radiation.

“The most toxic,” he said, “is chemotherapy. It requires four cycles. On day one, you’ll be infused with two chemicals. On day eight, you’ll receive one chemical, which is followed by one week of rest. In all, there are four cycles—approximately a two-month process.”

“How long do the infusions take?” I asked.

“Between two to four hours. Day one takes longer than day eight.”

“And the side effects?”

“Typically nausea, diarrhea, and fatigue although every person reacts differently.”

“Diarrhea,” I echoed. “Well, maybe that’ll help unclog my spillway.”

Later in the conversation, I expressed my interest in exploring the option of Death with Dignity.

True to his nature, Dr. Grivas was understanding. “That’s always your choice. I’ll have someone from our social work team contact you. You have stage-four cancer. If you do not undergo treatment, your life expectancy is three months.”

That prognosis raised my eyebrows. “And if I accept the treatment, how much time will that give me?”

“Everyone is different,” the doctor said, “but I’d say two years, give or take.”

***

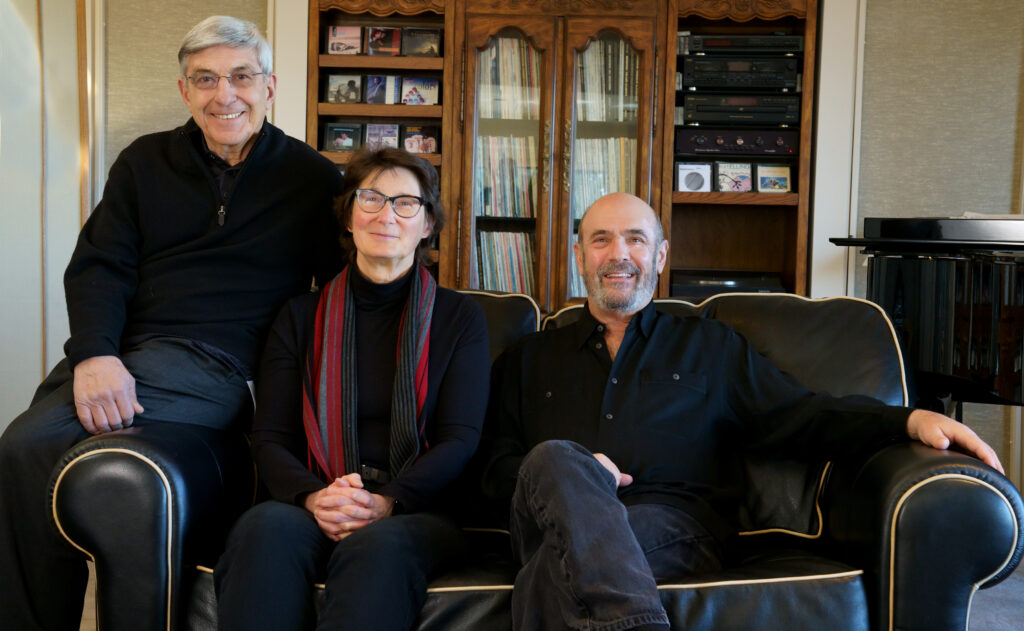

After the hour-long video call, my three neighbors came to our home to debrief. Nita also joined. We circled in the living room, sitting comfortably in leather lounging chairs and sofas.

“What do you think?” I asked.

Bob was the first to speak. “It seems straight forward to me. Play your hand before you fold.”

“Meaning?”

Bob lowered his gaze, sanded his hands, and turned back to me. “Look, Allen, the benefits outweigh the adversities.”

I turned to Alan. “And your take?”

Alan paused long enough to tug on his lower lip. “I agree with Bob. If the pain becomes too great to bear, you can always stop. But it would be a shame not to give treatment a try.”

I nodded, not necessarily in approval, but certainly in understanding. I shifted to face Elaine. “What are your thoughts?”

“I agree with Bob and Alan,” Elaine said. “Knowing the positive impact you have on so many, I think it would be sad to shorten your stay.” She took a deep breath and let it wither out. “In short, there’s more work to be done.”

“There seems to be a clear consensus,” I said, “but we haven’t heard from Nita yet.”

***

Nita was so quiet during our debriefing, it was almost as if she were not in the room. Parkinson’s Disease has a way of cloaking emotions. I could not read her face; there were no clues.

“Nita.”

She lifted her gaze to me. “Yes?”

“With both of us sick, we’re at a difficult place,” I said. “It’s complicated. I don’t know how I’ll feel during the treatments. Nor do I know how much I’ll be able to take care of you.”

Nita nodded.

“What’s your preference, honey? Would you like to stay with me? Or would you prefer to go to Oregon to stay with your sister?”

Nita did not hesitate. “I want to stay with you.”

I felt a catch in my throat.

She had more to say. “Of course, I want to be with you. But if staying makes your struggle more difficult, I’ll go.” Her eyes were beginning to shine. “It comes down to one thing: I want to do what’s best for you.”

Nita’s words shook me to the core. It was so like her: dismissing her needs and focusing on my wellbeing. How could I let her go? It was at that moment I decided to choose life, or as much life as I could coax out of my cancer-riddled body.

***

On February 23, 2023 I had my first chemotherapy infusion.

There have been times in my life when I felt insignificant if not invisible. In the early days living in France, when my senses were saturated with new sounds, images, and scents, I felt alone. How I wanted to express my wonderment, to walk up to a French man or woman and ask, “How is it possible that you and your country are so amazing?”

But I was incapable of stringing the words together. All I knew was “oui” and “non.” You can’t get very far with a vocabulary so daft.

The French are a timid people—a quality they might describe as “discreet.” They do not come rushing to tourists to help them find their way. That’s not a criticism. It’s a description of their cultural way of being. And so, I was forced to see, hear, and smell without fully understanding the richness of my experience. I might as well have been invisible, a ghost exploring a new world without the benefit of a French friend or even a buttoned-up guide.

Gradually, all that changed in proportion to the depth of my vocabulary. But the early days are still vivid in my memory—sad days with so much to share and no way to share it.

***

I offer that remembrance as a counterpoint to my experience at the Cancer Center in Kennewick, Washington—a clinic that administers fifty to sixty infusions every weekday. What I lacked in France I had in abundance at the Cancer Center. I was clearly visible and expertly served. I don’t think the King of Siam would have been treated more royally.

My sister-in-law Jan was gracious enough to accompany me. Jan is a woman whose sole purpose in life is to serve others, to find ways to lighten the heart and ease the pain. Nita and I are lucky to have her as a friend. I was comforted by her presence.

Jan and I waited in an expansive lobby for my name to be called. When it happened, I pushed up from my chair, turned the corner, and, in view of two attending nurses, performed a grapevine dance move, one foot crossing behind the other as I shuffled left and right.

Both nurses laughed.

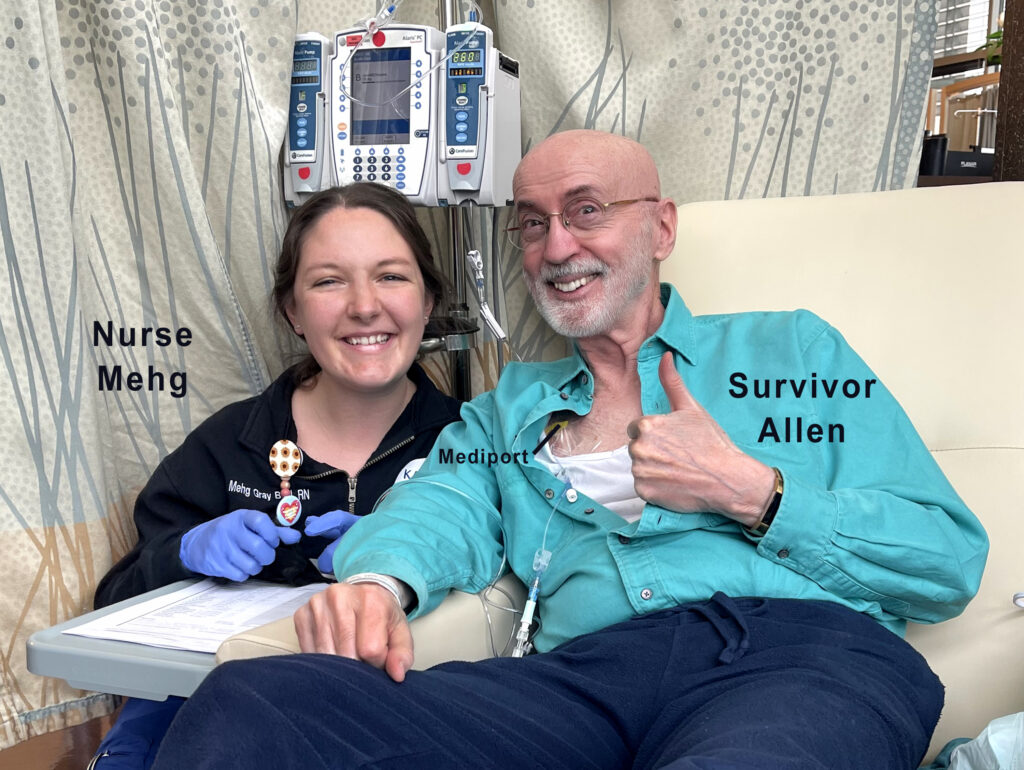

Mehg (an unusual spelling of Megan) was the registered nurse. Christy, the taller of the two, was a nursing student.

“That’s what I like to see,” Mehg said. “Enthusiasm.”

“It’s either that,” I said, “or thirty-nine choruses of ‘woe is me.’”

Mehg shoved her fists into her hips. “I’ll take the enthusiasm.”

Mehg made me feel as if I were the most important person on earth. Her voice was swift and bubbly, reminiscent of a child at Disneyland for the first time. “Let me give you the two-dollar tour,” she said.

The large room was organized with twenty chambers laced around an island of nursing stations. I was led to bay eleven. Happily, it was outfitted with an overstuffed lounging chair that, when motorized, provided support for the full length of my legs. To the left of my recliner was an electrical outlet within arm’s reach. That was a lifesaver. Over several months, I discovered that heat relieves my pelvic-floor pain by at least two notches. On a pain scale of zero to ten, my pain level is often a strong eight when sitting upright in a straight-back chair. When sitting on a heating pad in a lounging chair, my level of pain drops to a six or even a five.

The first ninety minutes were consumed with education. I was offered a two-inch three-ring binder with six tabs: My Care Team, Getting Started, My Diagnosis, Symptom Management, Resources, and My Records.

At one point, Mehg said, “You may lose your hair.”

“Is that a hair joke?” I asked with a wink as I swept my hand over my slick dome.

Mehg glanced at my white beard. “All hair,” she said. “Including face, chest, and right down to your toes.”

“Thank goodness,” I said. “Finally, I can stop shaving my legs.”

“Right,” Mehg said with a knowing smile. “Keep in mind, when it comes back, it could return in a different color and texture. Your beard could be black and curly. You never know.”

I waved off the prognosis. “Whatever happens will be fine. But the real question is can you poke a dimple in my chin?”

“Sorry, Allen. On that score, you get what you’ve got.”

***

The syringe slid into my mediport with ease. I didn’t feel a thing. The first medication infused was designed to combat nausea. Strangely, for a moment, I had the slight taste of what my brain registered as shoe polish.

The nausea medication was followed by two chemotherapies: carboplatin and gemcitabine, each of which took approximately twenty minutes to drain into my port. I felt and tasted absolutely nothing. The process was only interrupted when, on every hour, I wheeled my IV pole into the bathroom to relieve myself—the consequences of drinking sixty-four ounces of water every day to protect the integrity of my kidneys. You don’t want to make the kidney twins unhappy.

A highlight of the day was bonding with Murphy, a poodle-retriever therapy dog. He was a husky white animal, a strong two feet at his withers and three feet in length excluding his long feathery tail. I love large dogs—Nita and I had a clownish old English sheep dog earlier in our marriage—but Murphy took the prize for serenity and politeness. When he stepped between my legs and lay his muzzle on my knee, I caressed his head and neck with both hands, splaying my fingers into his wavy soft and downy undercoat. He looked at me with his dark limpid eyes as if to ask, “You wanna go for a walk?”

Can a therapy dog feel another’s pain? Although I’m no expert on the subject, I’d like to think so. I can say I felt a sense of peace as Murphy and I exchanged gazes. And I do hope I see him again. He and I have much to talk about.

***

When Jan and I left the Cancer Center, I felt at ease, resting in the hope the treatments would shrink the size of my tumors and relieve my pain. That would be good. But even if there is no change or, worse, if the tumors multiply, I will always remember the kindness rendered by the professionals at the Cancer Center. Their mission is truly a gift of compassion, devotion, and honor—a pledge that renders layers of visibility, a promise that coaxes tears of gratitude.