In 1972, Nita and I were living in a mountain village in northern Algeria, a region called La Grande Kabylie. The town was called Larbaâ Nath Irathen, formally Fort National. Sponsored by Mennonites, we both taught English at the high school for two years, a position that satisfied my military service as a conscientious objector during the Vietnam War.

But this story is not about me. It’s about Nita.

Nita has always had an all-embracing spirit. By that I mean her love for others has no borders, no prejudices, even when she is abused.

Each school day, we walked through the arched entry into town, and strolled past the grocery store, the butcher’s shop, and the mosque. The high school was on the opposite end of town.

Although Nita never said a word about it, she was the main attraction with her comely figure and long blonde hair. Work crews would stop, lean on their shovels, and gawk at Nita as if she were a burlesque dancer.

Nita never looked their way, but I did. I slowed my pace and stared them down. My look meant to say, “Back off. She’s not a vamp. She’s my wife and no concern of yours.”

But my threatening glare had no effect. They continued gaping at Nita without the slightest quibble.

One winter day, the cultural war crowned.

That morning, Nita’s hair fell down her back over a down jacket that closed at the waist. She wore cotton slacks over her leather boots.

Normally, Nita and I walked side by side, but the town portal was narrow, especially with the oncoming traffic of pedestrians, donkeys, and light trucks. On that day, I pushed ahead, Nita following, as we passed through the entryway.

Midway, Nita screamed—a shriek I had never heard from her before nor since. I whipped around. “What’s wrong?” I shouted.

Nita had her back to me. She poked her fingers at a lean man in a burnoose. “He swiped his hand between my legs.”

“Je n’ai rien fait,” the man said. “I did nothing.” Curiously, the man, who I put in his thirties, was not shouting. His voice was calm as if offering a polite greeting.

I was then, as I am now, a man of peace. I had never struck or even shoved another human being in anger. But at that moment, my gentle demeanor vanished. Although I hardly transformed into a smashmouth hulk, my jaw stiffened. I grabbed the man by his burnoose and slung him into the town side of the entryway.

“How dare you!” I barked.

“Je n’ai rien fait,” he repeated.

“I don’t believe you,” I said in French.

I pulled my arm back, ready to punch him in the face. But although my fist was cocked, it froze in midair. I looked over his shoulder at men who squatted flat-footed, smoking Gauloises cigarettes. Although dead still, their eyes fixed on the clash. Would I create an international incident by striking the cretin? Would I dishonor the peace mission of the Mennonite church?

I spotted a puddle of water, a remnant of an overnight rainstorm. I hooked my foot around his ankle and hurled him to the ground. At least that was my intention. It would have been satisfying to see him on his back, his burnoose soaking up the night’s cloudburst. But the man was nimble. Although he stumbled, he caught himself, stepped back, folded his arms, and smirked.

How I detested that sneer. I wanted to wipe it off his face, but I did nothing. I only said. “Tu me dégoutes.” You disgust me.

I took Nita’s hand, hooked it under my arm, and continued walking to school.

“Are you okay?” I asked.

“Yes. There will always be creeps wherever we go.” She turned her head to look at me. “How are you doing?”

“I’m angry,” I said. “For God’s sake, my teeth are chattering.”

“I know, honey. But I’m glad you didn’t punch him. You’re better than he is.”

I bit my lower lip. “I don’t know. Maybe. Right now, I still feel like clipping the stallion into a gelding.”

Nita recoiled and pinched the corners of her mouth. “Now you’re talking like a…well, like a man.”

“I beg your pardon,” I said with sham indignity. “You better watch your language, missy. Next thing you know, you’ll be calling me a brut.”

Nita snickered. “You said it. Not me.”

***

That was not the last time Nita was groped. A month later, a man pawed at her breast in the town’s crowded fabric shop.

Despite those torments, Nita’s integrity remained uncompromised. She stood serene and unshaken. When we talked about it, she said, “I have no control over their behavior. And bad manners—”

I cut her off. “Bad manners? Is that what you call it?”

“What would you like me to say?”

“I don’t know, how about ‘assaulting’ or ‘mauling’? ‘Bad manners’ applies to talking while eating or failing to say ‘thank you’ when someone opens a door for you.”

“Do you think roughing up the language would make depravity disappear?”

She had me. “No. It will never go away.”

“So why bother yourself with something that’s outside your control? Wouldn’t you rather be at peace than at war? After all, the only thing I control is my behavior.”

Self-control was not the only virtue Nita modeled. She was also the essence of diplomacy, patience, and forgiveness. Frequently, after composing an angry letter, I’d let Nita read it first. Invariably, her edits would turn down the heat. More often than not, after hearing her comments, I would trash the letter.

Today, it’s no surprise how she handles her challenges with grace. Although her words are now splintered, her steps unsure, she still has the finesse, the elegance to remain at peace.

What a woman.

***

There is another side to my Algerian story.

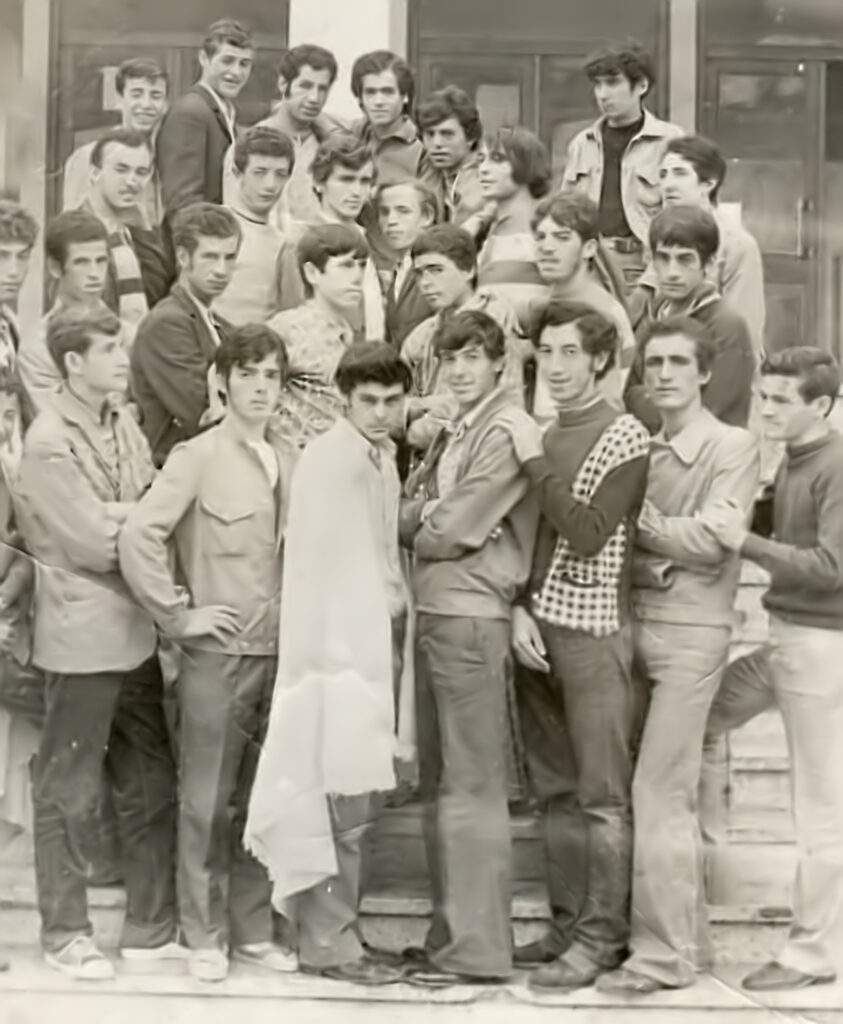

Several days after Nita was groped inside the town portal, I shared the incident with my English students. When I had finished, I looked across the room. They all had the same gaze: full of anger and shame for one within their tribe who had violated Nita.

One of my students failed to mask his rage. “Who did it, sir? Tell us his name, and we will take care of this.”

“I don’t know his name,” I said honestly. If I had known, I would have said nothing. My students—mostly seventeen- and eighteen-year-old young men—were loyal to Nita and me. And Berbers from that part of the country were known for their courage in battle. I hate to think what may have happened if they knew the thug’s name.

***

In 2023, three of my former Algerian students—Mohand Saïd, Youcef, and Zegane—managed to track me down and offer a humbling tribute. In their words, I had inspired all of them to become English teachers. Their praise moved me to tears.

From Mohand Saïd: “May God protect you, my friend.”

From Youcef: “Although you left Algeria in 1974, you will always remain my best teacher. You are my friend and brother.”

From Zegane: “Please know that all your former students adore you. You and your wife are still our idols. We think of you all the time. Oh, if only we could see you one more time before our lives are done.”

In another letter, Youcef said he would never forget the last school assembly when I stepped onto the stage with my guitar. I began with this greeting: “Je suis américain, mais ce soir avec vous, mes frères, je suis kabyle.” I am an American, but tonight with you, my brothers, I am Kabyle.

Now, forty-nine years later, I still embrace my former students. Then as now, I hope they are emotionally stable, intellectually fervent, and spiritually fulfilled.

Finally, I wonder if they would have held me in such high regard if I had spearheaded a movement to wreak revenge on the solitary bad actor who had dared to touch Nita. I don’t think so. If they loved Nita and me for any reason, it was not because we were vengeful but because we loved them back.