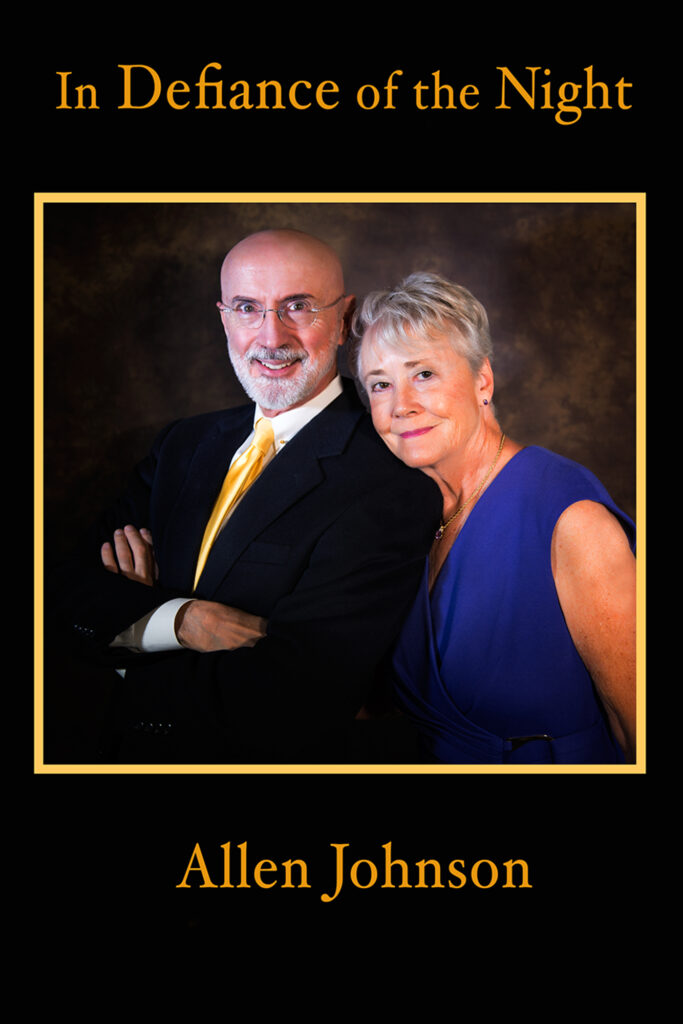

In the previous chapter, I shared a story that captured Nita’s courage in the early years of our marriage. Now, I’d like to affirm her valor in the precious twilight days of her life.

Nita is failing. There’s no getting around it. Overnight, she was unable to get in or out of bed without assistance. Her strength had dwindled to a faded memory.

After consulting with Josie and Alan—two members of our support team—I decided to call the Health Care Chaplaincy. On the following day, which fell on a Saturday, a registered nurse joined us. Her name was Amy. Also in attendance, via Zoom, was Nita’s sister, Margi.

Amy explained that Nita’s primary physician, as well as the hospice physician, came to the same conclusion: that Nita had less than six months to live—a condition that made her a viable candidate for hospice.

All of us stepped into our bedroom where Nita was stealing in and out of sleep.

At first, the conversation was academic. Amy described the hospice program. Our home would be supplied with a medical bed, a wheelchair, a commode, and an adjustable overbed table. She added a nurse would visit Nita once a week. Other resources would include visits by a chaplain, a social worker, and if desired, a shower aid.

It occurred to me that all these details might be overwhelming for Nita. I was about to say something when Alan stepped forward.

“Nita, how are you feeling about all this?” he asked

“Does this mean I’m going away?” Nita asked.

“Oh no,” Alan said quickly. “You’ll be right here in your home.”

The tension around Nita’s eyes slackened. “Oh, that’s good.”

About then, Alan left the room, was gone for a couple of minutes, and returned. A day later, I thanked Alan for addressing Nita’s concerns. “It was the right thing to do,” I said. “You saw her not as a lifeless object of curiosity but as a human being.”

“I had to leave the room,” Alan admitted. “I was so moved by Nita’s tenderness. I was afraid I’d weep at any moment.”

***

After Amy examined Nita, we returned to the living room. At one point, Margi questioned if Nita was starving to death—a considerate question from a loving sister.

The nurse was quick to respond. “Nita is not dying because she’s not eating; she’s not eating because she’s dying. Her body is shutting down.”

After signing several papers, all of which specified that Nita would be under the care of hospice, I said goodbye to everyone and returned to our bedroom.

I knelt at Nita’s side of the bed, searched her eyes, and posed a question that we often asked over the decades when we wondered if the other was at peace. “Are you a sad girl?” I asked.

Nita’s lips eased into a smile. “No, I’m a grateful girl. We have so many wonderful friends.”

“Yes, we do.”

There was a moment of silence.

Nita’s expression changed. It was subtle, but it seemed steeped in longing.

“Take my hand,” Nita said.

I caressed her hand and covered it with my own.

Then, without saying a word, Nita leaned in and kissed my palm as softly as a summer breeze.

The gesture was so tender, so trusting, so loving, my eyes puddled with tears.

***

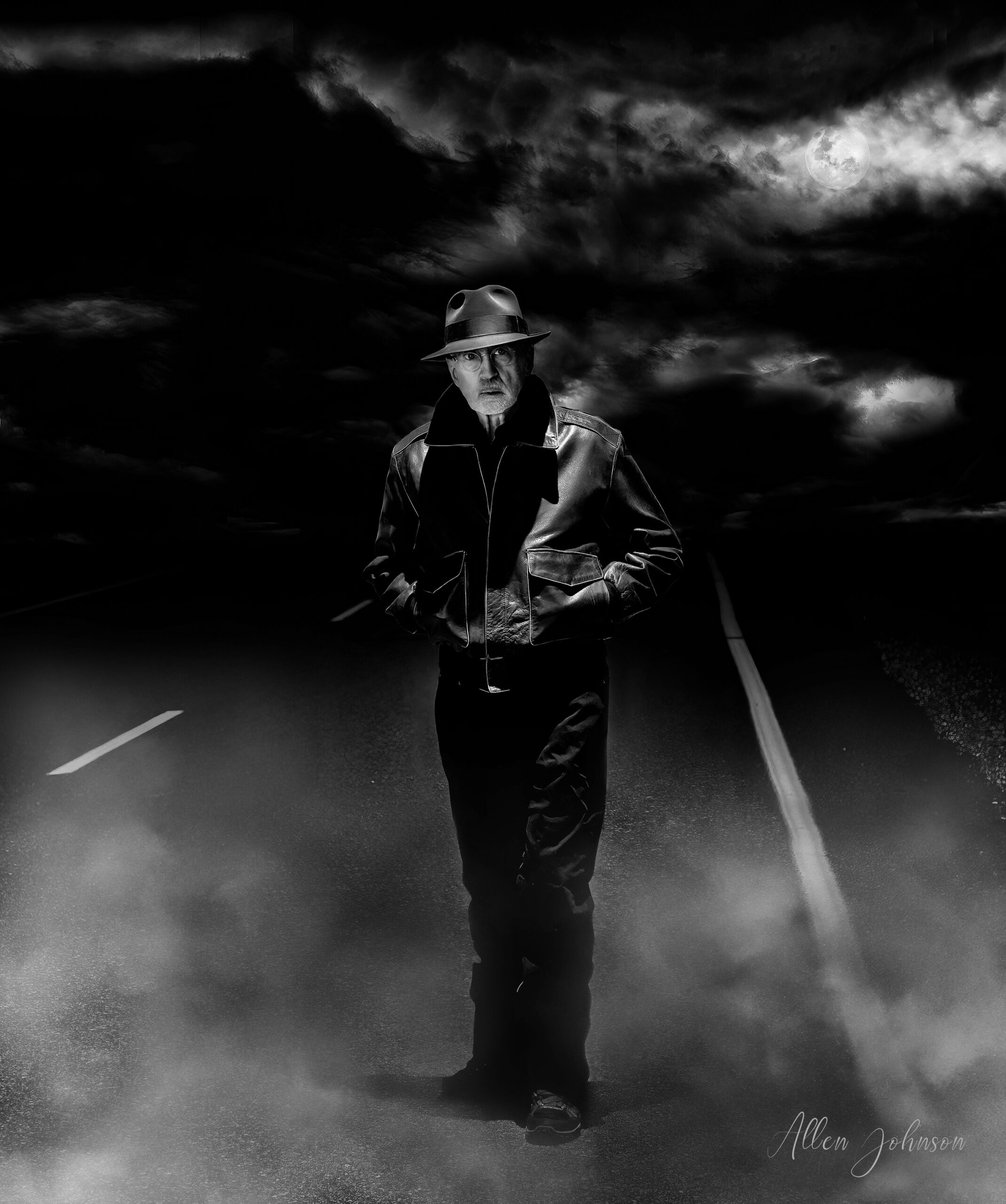

On the evening of the next day, I lay in bed with Nita at my side but not for long. My head swirled, my stomach clutched, and I was gripped by an all-consuming feeling of restlessness and existential dread. I slipped out of bed and shuffled into the living room, through the kitchen, into the den, and circled back to our bedroom. I crept into bed, closed my eyes, and the spinning, restlessness, and high anxiety slammed me again. It was as though a malevolent phantom levitated me above the bed and spun me without mercy.

Now, at 3:00 in the morning, I unlatched the front door and paced around our neighborhood, a half-mile loop. The fresh, sub-freezing air felt good. Maybe I’m okay. But even as I walked in the night, the fever returned.

I eased back into the house, peeled off my shoes, edged under our comforter, and closed my eyes. Again, I was breathless with anxiety. It was the most crippling and suffocating feeling I had ever experienced.

Now, my ego was at war. This is not like me. I can work through any problem. I have control of my body and emotions.

All that was hogwash. I controlled nothing.

The next morning, frazzled and bone-weary from lack of sleep, I called my palliative care practitioner, Angela. I described my condition.

“This is purely a self-diagnosis,” I said, “but this excoriates like a panic attack.”

“You’re right,” Angela said. “It’s not uncommon, not given your burden. Your body is letting you know you’re overloaded.”

My mind was in a fog. I could hardly recognize my voice. “I’m god-awful sick. And I’ve got to get some sleep. Is there something I can take?”

“I’d recommend Ativan,” she said. “It’s designed to relieve anxiety, and it’ll make you drowsy.”

“I’ll take it,” I said in a blistering tic.

“Hold on. There’s a drug interaction when taken with morphine.”

“Like what?”

“At worst, though the chance is slim, you could die. But if you still want to take it, I’ll prescribe a half milligram. That’s a very small dose. I recommend you take it at bedtime, two hours after taking morphine. It should activate in twenty minutes. I’ll send the prescription to your pharmacy.”

Before driving to the drugstore in a blue fog of anxiety, I researched the interaction between Ativan and morphine. The studies were mixed. Some highlighted the dangers. Others, including research from hospice, contended there were no risks when taking the two drugs simultaneously.

I was in so much misery, I took Ativan one hour after taking morphine and hoped I would awaken in the morning. With thanks to the chemists at Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, I slept peacefully through the night.

A couple of days later, I described my panic attack to my friend, Bill Leonard, a former principal for high school teens at risk.

“I’m not surprised,” Bill said.

“It surprised me,” I said. “What am I missing?”

“Come on, Allen. You’re a perfectionist,” Bill said. “For you, everything must be spot-on. Especially when it comes to your self-image.”

My chuckle was humorless. “Are you saying I’m wired a bit snuggly?”

Bill let a puff of air escape from the corner of his mouth. “A bit snuggly? Get real, Allen. There are mummies wrapped sloppier than you.”

***

My chemotherapy has not been without hitches. After the first infusion, my white blood cell count dropped precipitously. My second infusion was canceled and replaced with three abdominal injections over three consecutive business days. The drug was Neupogen, proven successful in stimulating the growth of white blood cells.

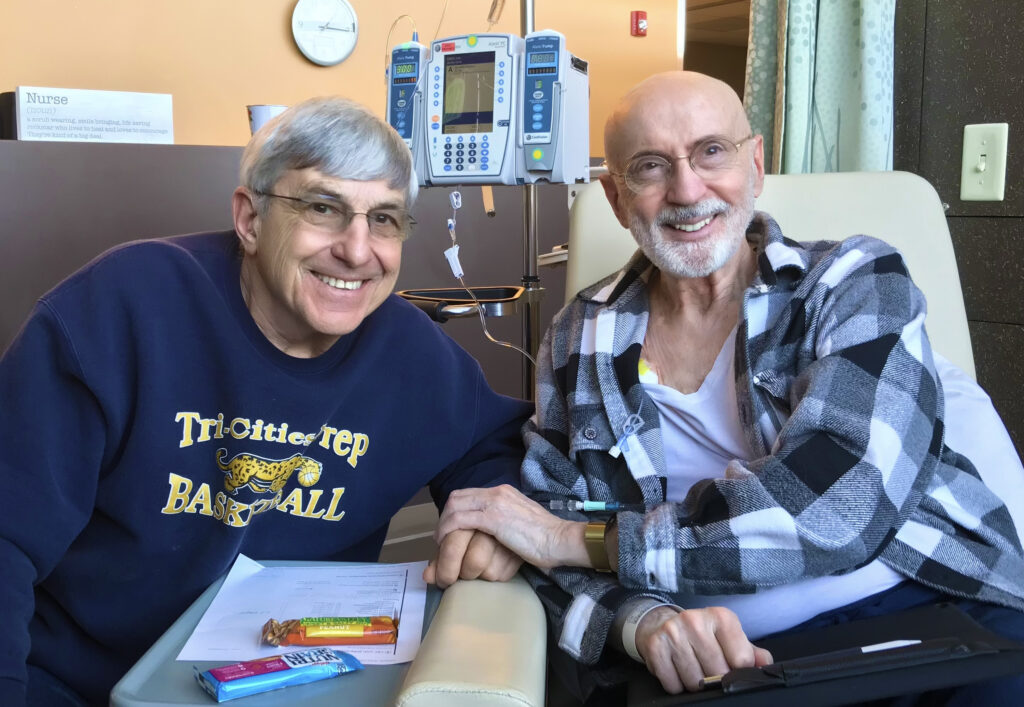

On the next infusion, I was accompanied by my friend and neighbor, Bob Rosselli.

I’d like to take a short diversion at this point. Our medical tribulations have not been faced alone. We’ve been blessed by a family of supporters who are the definition of integrity: those whose words are sealed by their actions. And each of them deserves recognition.

Bob has driven me four hundred miles round trip from our neighborhood to the University of Washington Medical Center—not once but twice. If that were not enough, he has baked and served his famous lasagna with only a hint of begging on my part.

So, to better understand this righteous man, I interviewed Bob while two chemicals were drained into my mediport. This is his story.

Bob was raised in Berea, Ohio, a small town sixteen miles southwest of Cleveland. His early education, from second through eighth grade, was held at a Catholic school that reinforced what he was taught at home: to be honest, dependable, responsible, caring, and hardworking.

At Berea High School, he was a three-sport letterman. In football, he played both ways as an offensive halfback and a defensive end. By the end of his 1962 senior season, he had scored the second-highest number of touchdowns in the greater Cleveland region.

After high school, he graduated from Baldwin Wallace College with a Bachelor of Arts in business, followed by an MBA at Michigan State University.

The interview rolled out easily, without bluster or one-upmanship. But I wanted to go deeper. “Tell me who you are without telling me what you do?” I asked.

“I’m a servant leader,” Bob said.

“And what does that mean?” I asked.

“It means I search for the creative third solutions that will satisfy the needs of both parties.”

Bob had a long and successful career with the Department of Energy, always in roles of leadership. But his contributions did not end there. He was a board member for a half dozen service-oriented organizations and a youth baseball, softball, and basketball coach for thirty-five years.

His background was impressive—woven in threads of fairness, compassion, and love—but I still held one final question for him.

“What would you like inscribed on your tombstone?” I asked.

He smiled. “That’ll take some time.”

Two days later, he emailed his tombstone epitaph. I nodded with favor when I read it aloud. “Robert Rosselli: A man always in pursuit of public victories over private accolades.”

***

Bob’s a good man. And if Nita and I manage these life challenges with any vestige of integrity, it will be by the grace of people like Bob: people who are willing to sacrifice their comfort for the needs of those who are approaching—reluctantly, contentiously, defiantly—the ominous passage to death’s door.

What is more, family and friends are not the sole servants of compassion. The staff at the Cancer Center are a special force of professionals whose mission could be: “We treat our patients as though they are the most important people on earth at this precarious time in their lives. Why? Because they are.”

As Bob and I drove home, I said, “I have the strangest feeling.”

“How so?” Bob asked.

“The irony is heavy,” I said. “Even though my body was infused with two liters of poison, I feel…enlivened.”

“Meaning?” Bob asked.

“I feel as if I were royalty,” I said. “Like a pampered prince from the golden age of Versailles. But there is one thing that bothers me.”

“What’s that?”

“When I head back home after two quarts of chemo, drivers don’t ever pull off to the side of the road to let me pass.”

“Well, that’s rude,” Bob said with a chortle.

“Exactly.”