I traveled to the University of Washington Medical Center with my trusted friend Bob, who directed me to the front door of the urology clinic. He also helped me frame the ordeal.

I had imagined the meeting would start with my world-class surgeon I’ll call Dr. Jennifer Seymour. I saw us seated on opposite sides of a conference table pouring over all of the surgical options. Would she be able to save my bladder? Or would it need to be removed?

That was not how it played out. The first person who came into the room was Nicole, a registered nurse with enough compassion to fill a football stadium.

“We’re going to start with a cystoscopy,” she said.

For those who don’t know—I was ignorant until I was diagnosed with bladder cancer—a cystoscope is a long, thin, flexible camera that is threaded into the urethra and into the bladder.

The first time a urologist explained the procedure, my eyes widened. “You mean, you’re going to ram a scope up my uterus?”

The doctor laughed. “No, your urethra. If it were your uterus, the operation would be considerably more complicated.”

What did I know? They were all mysterious U-words to me. All I knew was the procedure sounded as barbaric as being ratcheted on a rack over a bed of sulfuric acid.

Nicole prepped me for the examination, which naturally required me to undress from the waist down. There is one thing about bladder cancer: you soon lose any semblance of modesty. Since my diagnosis, a squadron of nurses have articulated, manipulated, and discriminated my most sacred region. Consequently, what was once Victorian chastity has faded into profane apathy.

Nicole injected lidocaine gel into my penis.

Five minutes later, Dr. Seymour tapped on the door and walked in. Why she knocked was a riddle to me. It was not as though I had a choice at the moment: “Oh, wait a minute. Let me tidy up.” Not likely.

“How are you doing?” the doctor asked.

“I’m not looking forward to this,” I said, trying without success to sound brave.

“Don’t worry,” she said. “I’m very gentle. And I’ll keep you informed at every step. Now, take a deep breath and wiggle your toes. If you think about your toes, it diverts your mind from what I’m doing.”

I wiggled my toes like a maniac. Believe me, I was not diverted. Still, I waved my toes throughout the procedure in the hope the digital mojo might save the day. It did not. My body tensed; my nose hairs flared. It was not fun. Although I managed to censor my profanity, if sin begins in the mind, I was ingloriously wicked.

The doctor explained what she saw on the screen, but I was not really listening. I was still focused on my useless feet.

At the end, Dr. Seymour pulled out the scope in a single tug. She must have graduated from the school of rip-the-Band-Aid-off. I responded with a whoop—not a curse but close enough.

“Sorry,” the doctor said as she left the room.

I was left with Nicole.

“You can go to the bathroom down the hall if you have an urge to urinate,” she said.

“May I put my pants on?” I asked.

Nicole hunched her shoulders, seemingly indifferent to my state of undress.

Although the nurse had seen everything there was to see, I was not ready to parade Mr. Willy for the rest of the staff. I slipped into my boxer shorts before shuffling to the restroom.

When I returned, I put on my jeans and shoes, uncurled my toes, and practiced my deep breathing exercises.

“Boy, I hate that,” I said to Bob. “I wouldn’t wish that procedure on zombie body snatchers.”

“I believe you,” Bob said in what sounded like a hushed prayer of contrition.

The doctor returned and sat next to me at a small table with a computer.

Before she spoke, I said, “You know, doctor, generally when I meet a woman face-to-face for the first time, I like to do it with my pants on.”

Her chuckle was more courteous than earnest. In fact, that was the only hint of humor for the rest of the meeting. What followed was a summary of sobering alternatives.

“I’m going to be honest,” Dr. Seymour said.

My face crumpled. Whenever a physician says ‘I’m going to be honest,’ the news is not good.

“Absolutely honest,” she added.

And when honesty is qualified,’ the news is catastrophic.

“The tumors in your bladder have migrated,” she said. “But that’s not the worst of it.”

“There’s something worse than that?” I asked.

“Well, maybe more frustrating than worse.”

“Go on.”

The doctor swiveled on her stool to look directly into my eyes. “We had planned to operate in a week.”

Before she finished her thought, I could feel my stomach flip. She was getting ready to cancel the operation.

“But I spoke with the internist regarding your blood clots,” she continued. “You’ve only been on Eliquis for a week. That’s not nearly long enough to tame the clots. If we operated on you next week, there’s an eighty percent chance of losing you. That’s not a chance I’m willing to take.”

Eighty percent was not a number that appealed to me either. “So, when do you recommend doing the operation?”

“I suggest one month from now—July 13. If we wait until then, the chance of losing you drops to only eight percent. I can work with that. Can you?”

I thought about an eight-percent risk. Would I cross a road if there was an eight-percent chance of dying? Probably not if it meant dashing to a café for a cup of hot chocolate. I’d wait for the light to change to give me better odds. But I’d cross in a second if, say, my wife were in danger.

In this case, I was the one at risk on the other side of the road. I was infested with cancer, and I had to do something about it as quickly as possible.

I didn’t like the idea of waiting another month. I thought about my cancer day and night. I wanted it out of my body. I’m an arrogant man. I pride myself in taking control of my life. But since diagnosed with cancer, my life was controlled by disease—or so it seemed. I had to get my mind off the wait, and focus on the procedure. “How should the operation be done?” I asked.

Her tone softened—nearly hushed. “My recommendation is a radical cystectomy.”

“What’s that?”

“The removal of the urinary bladder.”

The lines in my face deepened. “Where you cut a section of the intestines to create a new bladder?”

She nodded. “Or, as an alternate option, an ileal conduit, which would terminate with a bag on the outside of your body.”

I shook my head. “That’s not what I have in mind,” I said. “I’d like to save my bladder.”

The urologist took in a deep breath. “Your case is complicated for two reasons. First, your cancer is high grade. That means the cancer is more likely to come back.”

“How likely?”

“It’s hard to put a number on it. I would say seventy-five percent. Which means we’d need to look at the inside of your bladder every three months.”

“For how long?” I asked.

“For years.”

My future was looking increasingly grim. “You said my case was complicated for two reasons. What’s the second reason?”

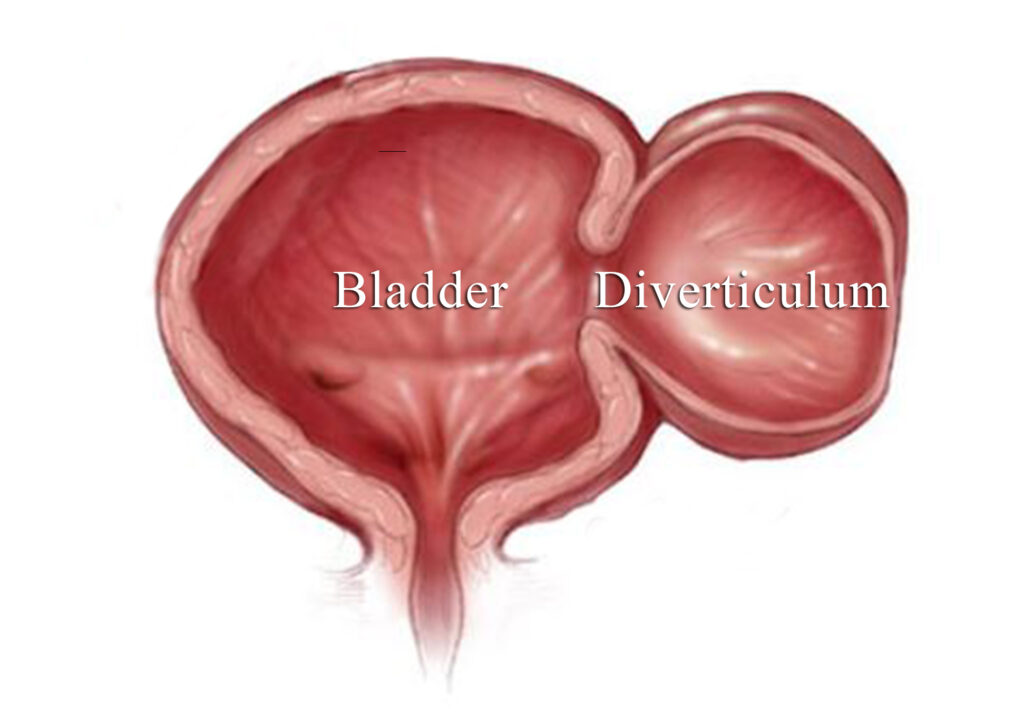

“You have a diverticulum.”

I tried to repeat the word and stumbled over the pronunciation. “What’s that?”

The doctor drew a picture. “There was a weak spot on the wall of your bladder. That weak spot ballooned out, forming a bulging pouch.”

“How big is the balloon?”

“About the size of a baseball. And it’s full of tumors. It needs to be cut off, what we call a diverticulectomy.”

I could feel my face heating up. I listened to the rush of air in my ears for a beat. “Look, I don’t want a bag on my side, and I don’t want a section of my intestines cut to form a new bladder. Can you save my parts?”

“It’s difficult,” she said, “but feasible. I would want to talk with my colleague who specializes in bladder reconstruction, but it can be done.”

“Then that’s what I want to do.”