On September 21, 2023, I offered a one-hour concert at the Cancer Center. With the mastery of Debi Eng on piano and her husband, Frank, on a pizza-box “snare” with brushes, we drew from the American jazz standards songbook from the 1930s and 1940s: “Fly Me to the Moon,” “I’ve Got a Crush on You,” and “Taking a Chance on Love,” to name three. When the last note was sung, the last cadenza played, hugs were shared as if we were all members of a larger family. And we were. I had never performed for such a loving audience. The laughter was free-flowing, the applause genuine. I felt like a soldier embraced by the citizenry of his hometown after a long, heartbreaking war.

How could that fellowship happen? It was because they knew me. They had read every chapter of In Defiance of the Night. They understood my sorrows, my heartaches, and my commitment to making a difference. They knew me and loved me—and I loved them back.

***

A day or two after the concert, I walked with my neighbor, Elaine, who had also attended.

“How did you feel about your performance?” she asked.

“I was excited,” I said.

“Are there times when you’re nervous?” she asked.

I expected the question. Elaine is one of my favorite people. Her reserve is an intriguing quality. I think she would agree that standing before an audience would be foreign, if not unnerving for her. But her public inhibition does not alter her ability to connect one-on-one; our warm relationship is the proof.

“I’m never nervous,” I said. “I’m always excited about the chance to perform, to give myself to others.”

Often, those who fear an audience subscribe to an outside-in perspective. Their minds are swirling in a boiler of questions: Will they mock my anxiety? Laugh at my blunders? Tire of my ramblings?

I don’t operate from an outside-in mindset. I take an inside-out attitude. In short, I ask, what is the greatest gift I can give to my audience? The answer is self-evident: be real, playful, and loving. If I’ve done that, I’m at peace.

“Your question has me thinking about my fears,” I said to Elaine. “I’m not afraid of heights, darkness, or even death. Nor do I fear audiences because I know my honesty and gentleness of spirit will always be received with a grateful heart.”

“Surely, you must have one fear,” Elaine said.

I thought for a moment, and then it came to me. “Yes,” I said. “I’m possessed by one trepidation. I’m afraid I might not connect with others when the invitation is offered. What a tragedy that would be.”

This is my prayer: Let my mind be alert; let my heart be open. Let me cherish the knowledge that emerges from every new encounter. And let me have the humility to incorporate their wisdom into my way of being.

***

Elaine often expanded my knowledge as was made evident at the end of our walk.

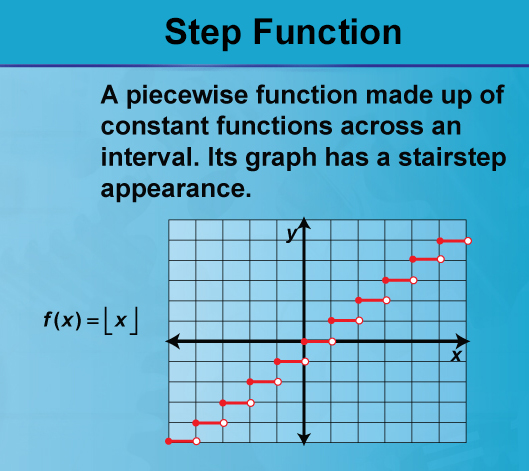

“I find my health to be a series of declines and plateaus,” I said. “I’ve been on a two-month plateau, defined by fatigue and shortness of breath. But in the last week, I’ve experienced a new step-down. My saliva is excessive and my speech is slurred. It’s as though the seven tumors in my brain were doing the macarena while I’m relegated to an assisted-living facility in Arizona—content to entertain the other wheelchair tenants by blowing spit bubbles and pumping musical armpit noises.”

I paused long enough for Elaine to grasp the images. “Yes, the drooling is annoying,” I said. “My speech blathers and my singing gurgles, but I refuse to be undone. Not now, not yet. Every step down and plateau are part of a plan. I sensed the hostility before I had a name for it. I know the name now. It’s called dying—an entanglement which may fester for seasons to come.

I was not sure Elaine was following. Nita came to mind as the perfect example. “I witnessed Nita’s plateaus,” I said. “At first, she was able to write until writing was no longer possible. Still, she managed to walk until walking was hopeless. But even when she was bedridden, she could speak until she could no longer string words into a lucid sentence. Each step down was followed by a period of little change.

“There’s a term in mathematics for what you’re describing,” Elaine said.

“Be careful,” I said. “Remember, I was a literature major.”

Elaine flashed a dubious glance. “It’s not that tough. The term is ‘step function.’ It’s defined as ‘a function that increases or decreases abruptly from one constant value to another.’”

“Step function,” I repeated. “That sounds like me. My garbled speech is a step function down in my health, and there will be more to follow. I think the trick is to enjoy what I have while I have it. There’s no other choice.”

We walked in silence for a while. When we reached my home, Elaine gave me a hearty embrace. As she held me in her arms, she said, “There are no strangers in your life, Allen. There are only people you have not yet met. I’m so glad we’re friends.”

I stepped back so Elaine could see my crooked smile. “Me too,” I said. “Before meeting you, I never knew mathematicians could actually speak.”

Without hesitation, Elaine said, “We not only speak but count the words we say when we say them.”

“Oh, yeah?” I asked. “How many words was that?”

“Fourteen,” she said with attitude.

And fourteen it was.