The operation took six hours. By the time I was wheeled into my room on the seventh floor of the University of Washington Medical Center, it was five o’clock in the evening. This is what I remember of that first night.

The nurses hoisted me from one bed to the other by virtue of an overhead lift and track system. For a moment, I felt like a thoroughbred racehorse lifted to protect his torn ligaments. I floated down like a feather. I was happy. There was no way I could have transferred myself—not the way I was drugged.

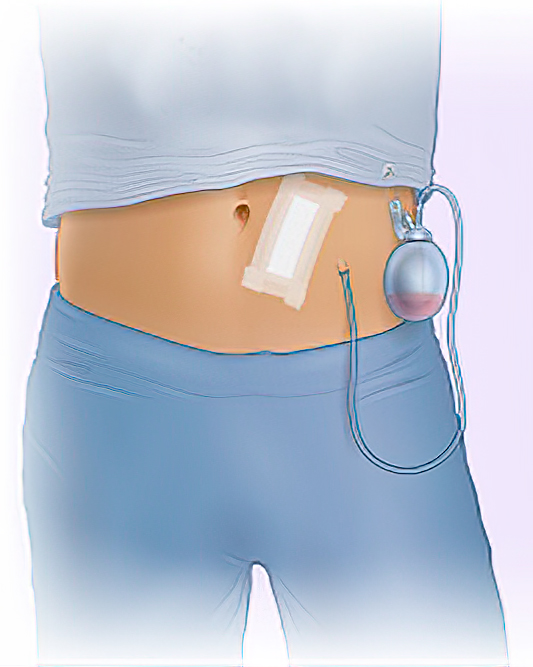

I slept the rest of the night and into the next day. When I awakened, I had a six-inch vertical incision directly under my navel and two IVs, one in my left hand and a second in my right wrist. In addition, two tubes extruded from my body. The first was a Foley catheter from my penis to a butterfly clip to a bag of urine. The second tube, called a Jackson Pratt drain exited below and to the right of my navel. At the end of the short JP-drain tube was a clear bulb—sometimes call a grenade for its appearance—that suctioned peritoneal fluid from the abdominal cavity.

In all my life, I had never been so poked and yoked—and so utterly helpless. And yet, on the morning of the first day, the nurses told me I needed to stand up and go for a walk. “Walking is the best way to heal,” I was told every day for a week.

I did not get out of bed—not in the traditional sense. I rolled unto my side, let my legs slip off of the bed, and righted myself by pushing off from the hospital-bed railing. I was painfully slow.

The walking route circled the long nurses’ station. One lap required 122 strides; I know because I counted the steps—but not on the first day. On my first trek, a physical therapist cinched a belt below my chest (to have something to grab should I stumble), and instructed me to set my forearms upon a wheeled support walker. I shuffled along for three laps on that first outing and was proud of my accomplishment.

After that, I kicked the walker. I was on my own. I soon built up to five six-lap tours a day. I was known as the most motivated patient in the ward, and I was pleased. As the days passed, I would tease the nurses in the hallways.

“Beep, beep,” I said. “You’re going to feel a breeze when I whoosh by. You may want to hold down your hair.” I would have said “hold down your skirt,” which would have been funnier, but all of the nurses wore pant scrubs. I was the only person in the ward wearing a skirt—with legs as beguiling as ham hocks.

One day, as I loped down the hallway, my nurse for the day, Casey, said, “There you go again.”

Being a flaming extrovert, I stopped. “Casey, you’re reminding me of a great 1940 Vernon Duke tune.” I punched my fists into my hips in sugar-bowl style and sang.”

“Here I go again.

I hear the trumpets blow again.

All aglow again,

Taking a chance on love.”

Casey’s eyes were shining. “You get out of here before I fall in love with you.”

I’m guessing nurses are not serenaded all that often. What a shame.

***

Dr. Seymour came to see me at the end of the second day.

“Hello, Mr. Johnson,” she said.

“Hi.”

“How are you feeling?”

“Like somebody gut punched me.”

“That’s normal.”

“Not for me.”

The doctor smiled. “I want you to know the surgery went perfectly. It could not have gone any better.”

“I was surprised to see so many people in the operation room,” I said. “Was there a time when two sets of hands were in my tummy?”

Dr. Seymour jerked her head back but only by an inch. “More like four sets of hands. It’s a team effort.”

“Wow! It’s going to be tough getting that image out of my head. I feel like I was the family punch bowl for bobbing for apples.”

“A little more sophisticated than that.”

The surgeon did not stay long, but for the few moments she was there, I felt I was the most important person in her life.

***

All the nurses—Chelsey, Casey, Carolyn, Kelli, and my only male nurse, Zane—were sensational. They were powerful and loving creatures, willing to tend to the most mundane and often demeaning tasks, including the cleaning and disposing of body fluids and solids.

They were also creative.

After lunch one day, I had a piece of chicken lodged between two molars. “Would you have any dental floss?” I asked.

“I’m not sure,” nurse Chelsey said, “but I’ll look for you.”

A few moments later, Chelsey returned. “I’m sorry, we don’t have dental floss, but I thought this might work.” Opening her hand, she presented a tea bag with, naturally, a string attached to accommodate steeping.”

I took the tea bag and snapped the string. It held. “You’re a marvel,” I told Chelsey. “What a crackerjack mind. I can’t think of anything more creative. Well, I suppose you could have plucked a hair from your bangs. But then I’d be thinking about shampoo and hairspray. Nah! The tea bag was definitely the best choice.”

I could hear her tittering under her mask.

“I do what I can,” she said.

Nurses are not only creative; they’re also an easy audience.

At seven in the morning and seven at night, the nurse from the previous shift would enter my room to introduce me to the incoming RN.

“What?” I’d ask the outgoing nurse. “You’re dumping me off on somebody new—now in my time of need when I’ve been so vulnerable, so ashamedly exposed. Now that you’ve had your way with me, you cast me aside? Go, thou despicable wench. Fly away.” I allowed my voice to break up. “See if my heart tolls a single beat of sorrow when you’re gone.”

It was all blatherskite. But how I loved to play it up because I always got a chuckle from both nurses. And there’s nothing sweeter than giggling angels of mercy.

The longer I stayed—six days in all—the more I thought less about myself and more about the professionals who served with such compassion.

After I had composed the question in my head, I turned to nurse Kelli. “I’ve been thinking about you,” I began.

“Now, stop that,” Kelli said. “You’re sweet, but I’m already married and so are you. Even if we were both single, it would never last. After three days of listening to your whining, I’d give you up for Lent. So there.”

I shook my head. “Oh, you’re a hard woman, but actually I had another thought in mind.”

“I’m listening.”

“In your profession, all of your relationships are brief. I’ve been wondering if there is ever a sense of grief when a patient leaves.”

Kelli thought for only a beat. “No, there’s no grief. As much as I love my patients, I can’t take sorrow back to my home, to my husband and children who love me.”

“Of course you’re right,” I said.

“But there is a shade of longing.”

“For what?”

“For the patients’ well-being, for their good health, for a life vaccinated by love.”

“‘Vaccinated by love,’” I repeated. “You just can’t kick the medical jargon.”

“I’ve been a nurse a long time.” She took a step closer to my bed where I lay. “In a way, I think of my patients in the same way I think of my children. One day, my kids will leave to make their way in life. I will obviously miss them, but I will also celebrate their departure. It would be cruel if I held them back.”

I nodded.

Her eyes became more intense. “And when you leave that will be a celebration too. You’ll be stronger. You’ll be going home to the people who love you. And that’s why I do what I do.”

Because she was wearing a mask, I glimpsed at the photograph on the identification card draped from her neck. “You’re a beautiful woman,” I said. “In a host of ways.” I paused to gather my thoughts. “Will I see you tomorrow?”

“No, Allen, I have a few days off.”

“In that case, I want to tell you how much I enjoyed your company. You’re not only a consummate professional, but a master of compassion. I know you care about me as a patient. But I also know you hold me dear as a human being. I see that in your tenderness, in the even keel of your spirit. Please know you’re a treasure.”

Kelli held both hands over her heart. “Thank you, Allen. It’s not often I hear such praise. I’ll remember you.”

“And all this time, I thought I was completely forgettable.”

She cocked her head. “Now, you’re fishing for a compliment.”

“Not really fishing,” I said with a broad grin. “More like trawling. You get a bigger catch that way.”

She wagged her finger at me. “I think it’s time I checked up on my less demanding patients.”

She was gone, and I was left skimming my hand against the stubble at the back of my head. Nursing. Perhaps the highest-value profession at the lowest tier of appreciation—truly the unsung heroes.