It happened at the executive staff meeting. I was presenting a new organizational development program, and it seemed to be going well. At least the staff of twelve was attentive, occasionally nodding in approval.

When I had finished, the CEO said, “This could make a big difference in our company,” he said.

“I think you’re absolutely right,” I said offhandedly.

Then—curiously, unexpectedly—the CEO turned to me and said, “I don’t give a shit what you think.”

That snapped my head back. What could he be thinking? Why would he berate one of his employees before his executive staff?

I tried to relieve the tension. “Are we going to have a donnybrook right here and now?” I asked with a befuddled smile.

The CEO glared at me with snake eyes and said in a husky whisper, “Don’t even try.”

What would you do next?

I’ll tell you what I did, but not before introducing a model for dealing with organizational conflict—conflict of any kind really.

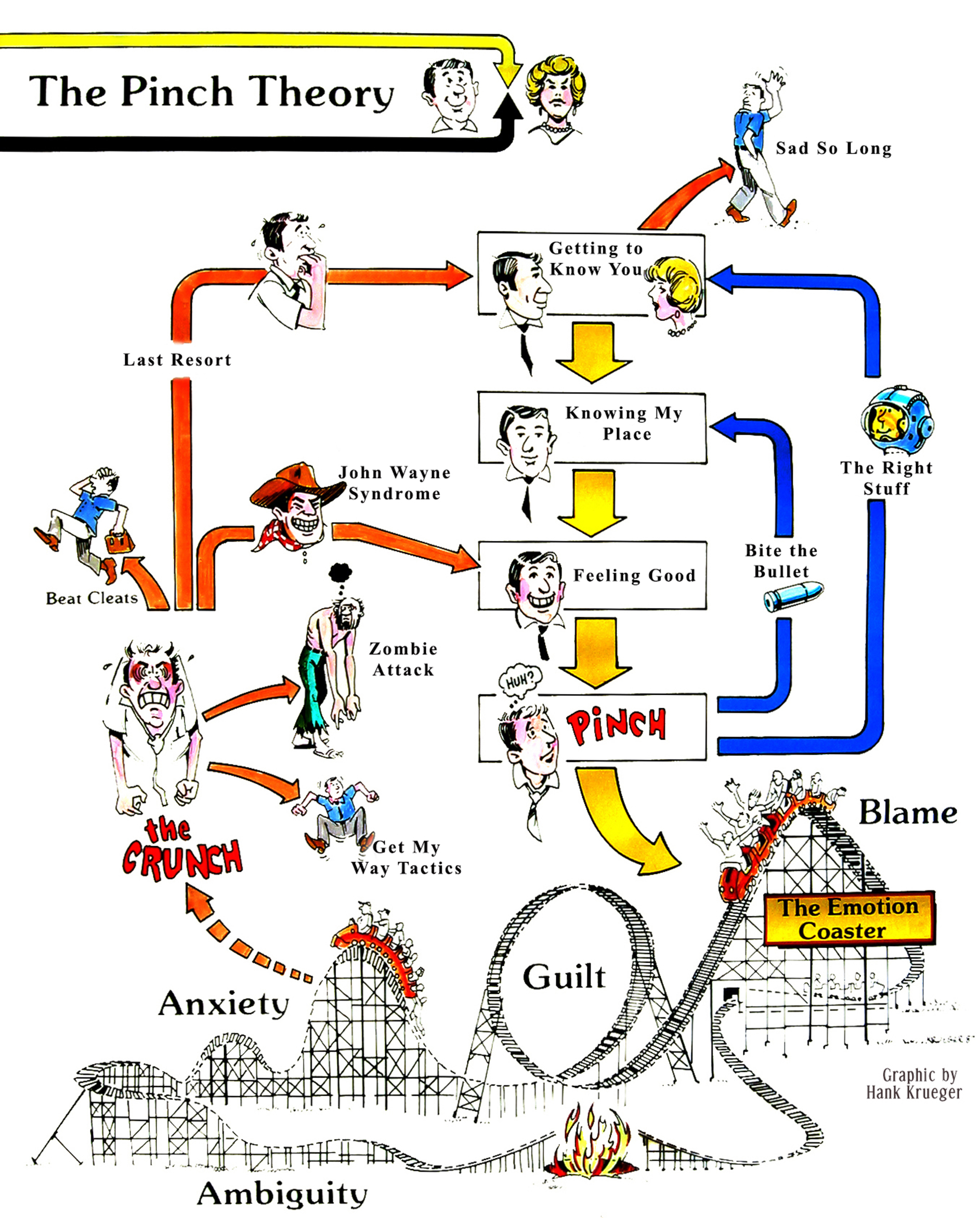

It’s called the “Pinch Theory” and was first developed by John Sherwood, John Glidewell, and later extended by John Scherer.

On the road to pinches

Whenever individuals enter an organization, they invariably spin through a cycle of optimism and disappointments. It begins when the employee and the manager—or co-workers for that matter—meet for the first time. At that first encounter, they are “getting to know each other.” During this honeymoon stage, they both want the relationship to work, so they’re on their best behavior. If something doesn’t feel right, they simply ignore it.

In those early meetings strong managers establish their expectations. Consequently, the new employees “know their places” and “feel good” about it.

But that happy feeling is generally short-lived. After a time, the first “pinch” is felt—especially in organizations where expectations are unclear.

A pinch is the unsettling feeling that something is wrong, that expectations have been violated. We might say to ourselves, “Hey, what was that all about? I thought we were on the same side.”

A pinch may come in a word or a look: a snide remark, a subtle put down, or even a sideways glance.

What do we do with a pinch? Typically, we “bite the bullet.” We say to ourselves, Wow, that smarted, but I’m an adult. I can handle it. We remind ourselves of the early days, when we knew our place and felt like a valued team member. In other words, we sweep the pinch under the rug, until an expensive consultant trips over the corrugated carpet, takes a peak, and watches in horror as all the bats from hell whoosh out with gleaming fangs.

A pinch does not vanish when it’s disregarded. It shows up later in uglier ways, taking us on a harried “emotion coaster.” Those emotions include ambiguity (What did the boss mean by that?), guilt (Gee, I must be doing something wrong), blame (It’s not my fault the boss is an idiot), and anxiety (I’m having a helluva time sleeping these days).

This is not a happy time for employees. It’s a debilitating roller coaster ride that ends in a “crunch”—when the mounting pinches are unbearable.

Irresponsible responses to a crunch point

Those who have been repeatedly pinched will often resort to “get-my-way tactics.” Some will turn to depression, believing that their depression releases them from responsibility. Others may choose anger by deriding the management team or even sabotaging the company’s mission. Still others will self-medicate—turning to alcohol, drugs, or comfort foods for relief.

These are all get-my-way tactics. The victims hope their depression, anger, or addictions will magically stop the pinches. They won’t.

Others may emotionally check out, stalking about like “zombies.” They are human, but just barely. Don’t ask them to do anything, because it will be done badly, or not at all.

The hardiest of the lot channel “John Wayne”: “That really hurt, pilgrim, but I’m gettin’ back on my horse and doin’ it again.” Recalling their satisfaction in “knowing their place,” they try to recreate it. Unfortunately, when pinches are ignored, the wounded employee will return even faster to another crunch point.

A few will “beat cleats.” They will update their résumés and take the first job that comes along. They leave without resolving the issues. And, not surprisingly, carry their resentments and lack of understanding to the next position.

Doing the right thing

What is the right thing to do when employees reach the crunch point? The answer is what the graphic calls the “last resort”: talking to the boss. This option requires both consideration and courage: consideration in clarifying our manager’s expectations and courage in describing our own “emotion coaster” ride.

There are two possible outcomes to such a negotiation. In the first and best outcome, gifted managers will calmly examine mutual expectations—seeking first to understand and then to be understood. They will also create a strategy for addressing future pinches.

In the second possible outcome—when their expectations are incompatible—the manager and employee will agree to terminate their relationship—to say “so long.” If it comes to that, they leave disappointed, but wiser. Understanding the sticking points will aid the departing employee on the next job.

The truly right stuff

The smart people—the ones who understand the pinch theory—will do the “right stuff.” They will not wait for the crunch. The first or second time they are pinched, they’ll seek out the manager (or the employee) and clearly and fairly describes the pinches. Hopefully, the manager will have the wisdom to clarify expectations and own his or her own shortcomings. When that happens, both manager and employee can return to a workplace of trust where problem-solving is a piece of cake.

When to do the right stuff

Deciding when to initiate the “right stuff” is not always easy. You must consider both risks and benefits, which requires honest self-evaluation. Here are five crucial questions:

- How important is the relationship?

- How important is the issue?

- What will happen if I do nothing?

- How will I feel about myself if I do nothing?

- Is the other mature enough to examine expectations?

If we are talking about your boss, the answer to the first question is “important.” The hours we put into a workday warrant healthy relationships. The second question is pivotal: How important is the issue? If the pinch is trivial—a failure to return a morning greeting, for example—the issue may be innocuous and unimportant. However, if the issue is chronic and acute, doing the “right stuff” is prescribed.

Employees should also consider the consequences of inaction. Will the pinches continue? Will the irritation fester? Will the success of the company mission be jeopardized? Will the employee feel disrespected? If the answer is “yes,” it is time to do the “right stuff.”

The game changer may be the last questions: Is the other mature enough? Even if the relationship and the issue are important, even if the outcome of inaction is toxic, doing the “right stuff” may not be a valid alternative. It may be wiser to simply leave—to “beat cleats”—which essentially means leaving mad and ignorant. It’s not the best alternative, but it may be the best option, given a hostile environment.

The path I took

I never did the “right stuff” with my CEO. Although the issue was important, I did not think the executive had the maturity to have an honest and respectful discussion. I reasoned—rightly or wrongly—that he was imbued with a stubborn ego. (He may have thought the same of me; I’ll never know.)

So, on that very day, I updated my résumé. The hunt was on.

As it turned out, the CEO left the company shortly after that infamous executive staff meeting. It was no longer an issue. He was gone.

It was unfortunate I could not speak to him, nor he to me. He could have learned how he was violating my expectations. More importantly, I could have learned how I was missing the mark. Consequently, the relationship ended unresolved and steeped in resentment, at least for me, which is never healthy—certainly not the best way to deal with the inevitable pinches of business life.