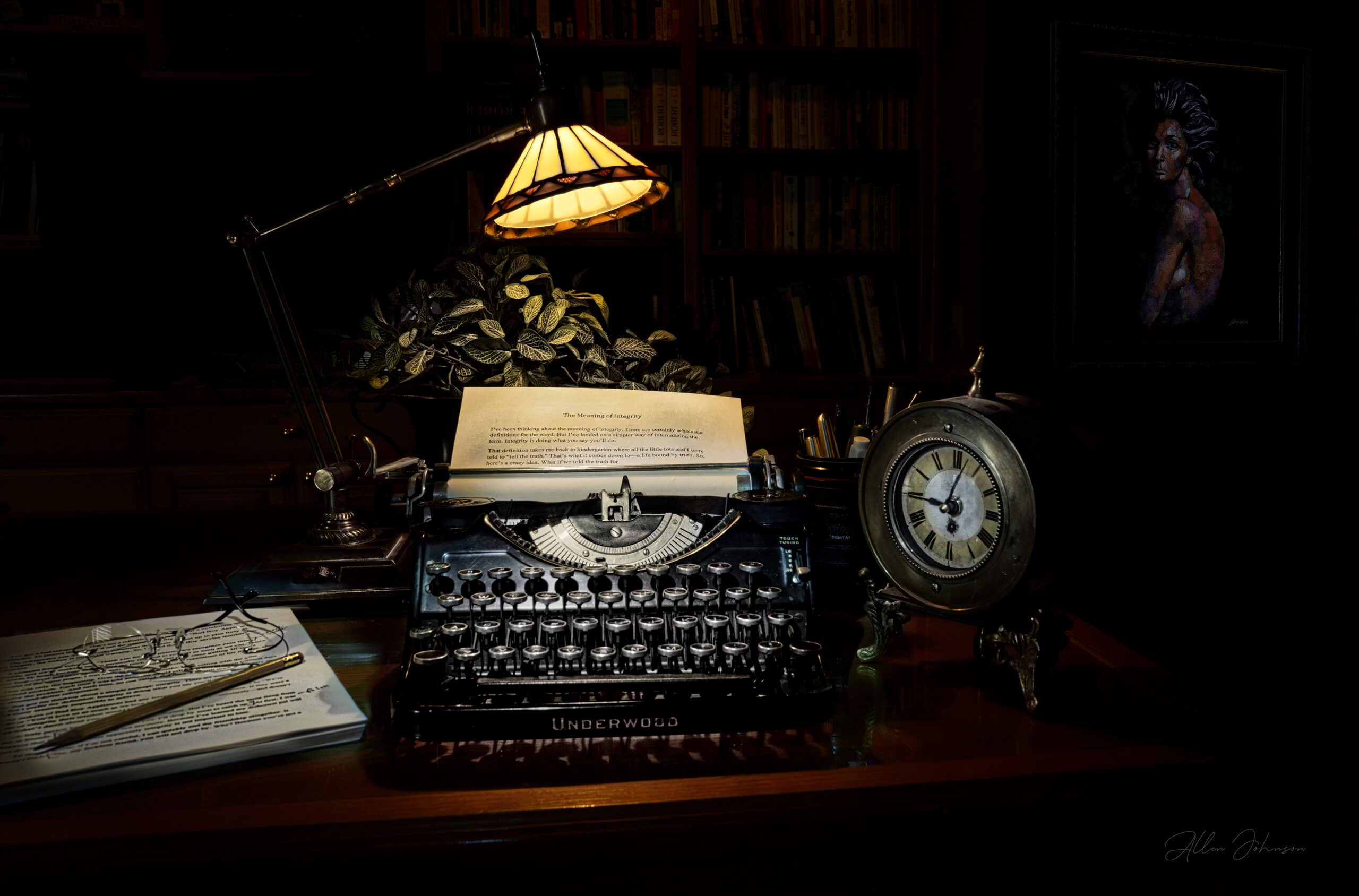

When I was in college, I typed all my papers on a Royal manual typewriter, resplendent with a gray case with a detachable lid. Each key stroke was a two-inch drop to raise the blade and snap the letter onto the paper.

Today, I would never use a manual typewriter. If nothing else, I am spoiled by the backspace key on a keyboard that magically erases every errant letter. But there is one thing I miss with a keyboard: the tinkling bell at the end of every line. Ting. And then there was the sweet satisfaction of reaching for the carriage return lever and slamming it home to the right. It was constant reinforcement—a pleasant, reassuring chime that rang with every line of work accomplished.

Friendship should be like a manual typewriter. You do the work, and you are rewarded. Now I know there are those who would say, “Friendship should be given freely, without expectations.” I have a word for such critics: “Baloney.”

There is a law of reciprocity. To put it simply, kindness engenders kindness. That is the wonderment of friendship: you can count on me, and I can count on you.

That’s the law. But, as we all know, laws can be broken. When that happens, when kindness is not returned, it is not true friendship; it is social slavery. The consequences are grave—a damaged or even shattered friendship. Once the law is broken, it can take weeks, months, or even a lifetime to repair, if at all. Victims of such violations may be civil, but are unlikely to be warm.

When developing friendships, my first priority is to honor the law of reciprocity. For example, over the last month my wife composed our will. One of the requirements was to identify a personal representative, made more difficult by our childless status. Happily, we had someone in mind. Fifteen years younger, she was a woman of intelligence and integrity, the perfect attributes. When I asked if she would be willing to take on the task, she said, “I would be honored.” When I explained that we wanted to repay her services by including her in the will, she was stunned, saying she only wanted to help.

“I always honor the law of reciprocity,” I explained to my generous friend, “even if the exchange is done after death. Why would I ask so much from a friend and not give something back in return? By honoring the law of reciprocity, I’m honoring the spirit of the golden rule.”

That’s the first law of friendship. The second law is empathic listening.

Empathic listening is like working on a keyboard. There are no bell sounds at the end of the line. Nor do you have to return the carriage. It’s all done automatically, from one line to the next.

Empathic listening is like that. The work is constant—unending. You simply listen. You don’t interpret, you don’t judge, and you certainly don’t use your friend’s words as a springboard for your own agenda.

When I ask an audience who among them are excellent listeners, half the participants raise their hands. They have overestimated their skills. According to the American Family Therapy Association, only one person in ten thousand is an excellent listener. I believe it.

Here’s how people typically “listen”:

Speaker: “I just don’t understand my wife anymore. Whatever I do, I can’t please her.”

Poor listener: “Yeah, I know. I have the same problem. I tell my wife I have to work late and she doesn’t like it. Then, I tell her I’m taking a day off from work, and she blows her top. There’s no way I can win. Let me tell you what happened yesterday . . . “

Now, let’s see how an excellent listener handles the same scenario.

Speaker: “I just don’t understand my wife anymore. Whatever I do, I can’t please her.”

Good listener: [Silent, but focuses more intently on the speaker.]

Speaker: Yeah, like the other day, I asked her if she wanted to go out to dinner.

Good listener: And . . . ?

Speaker: And, she said, “So, what’s wrong with my cooking?”

Good listener: Hmm.

Speaker: But, now that I think about it, I think I did criticize her lasagna the night before. Well, I didn’t really criticize it. I just said it wasn’t like Mom’s lasagna. Maybe that was a stupid thing to say.

In brief, a good listener simply seeks to fully understand the speaker. Eventually, one of two things will happen . Either the speaker solves his or her own problem (as in the example above) or asks for advice. Now, when advice is solicited, a good listener has license to offer his or her ideas, but with caution. Excellent listeners know when even solicited advice is no longer welcomed—when they have moved from advising to meddling.

Seven hundred and fifty years ago the great philosopher and theologian, Thomas Aquinas, said “There is nothing on this earth more to be prized than true friendship.” I applaud that sentiment.

One way to protect true friendships is to remember the analogies of the typewriter and the keyboard. First, like hearing the bell on a manual typewriter at the end of line, reward kindness with kindness. Second, like the steady flow of fingers moving methodically over a keyboard, keep listening seamlessly to understand.

I really don’t think anyone needs anything more to maintain a true friendship: reciprocity and understanding. Say it out loud and make it so.